American Strawberry Bush, (Euonymous americanus), is the native version of the invasive Burning Bush (Euonymous alatus). This stunning 5’ tall plant sometimes called Bursting-Heart, is super showy in fall with scarlet fruit capsules opening to show orange seeds inside.

Late Flowering Boneset (Eupatorium serotinum) is a 5’ tall plant covered in small white flowers from September through November. Its long narrow leaves are a beautiful gray-green color. Its a great source of nectar late in the season for bees and butterflies. Salt and deer tolerant too.

Another great pollinator plant, Flat-Topped White Aster (Doellingeria umbellata) has big clusters of white flowers with chartreuse green centers in August and September. It is the host plant for several butterflies and moths including the rare Harris’ Checkerspot. It gets up to 4’ tall.

One of my favorites, Pasture Thistle (Cirsium discolor) is just what you think, one of the thistly purple plants seen growing along roads. This genus contains many pernicious weeds but this one is a good one. Find the right spot for this, and you’ll be rewarded because this tall purple fall bloomer is the host plant for Painted Lady butterflies, is a bird and bee magnet and the seed ‘fluff’ is used by goldfinches for nesting material. Grows just about any sunny spot, but its thorny so put in in the back of the border. The thorns keep the deer at bay.

The not so subtle giant Cup Plant (Silphium perfoliatum) gets to 7’. Perfoliatum means the leaves surround the stem, in this case forming ‘cups’ that catch water. You’ll find birds drinking from this after a rain. This hefty plant needs space, but in return will give you flowers all summer long. Attracts butterflies, skippers and bees and provides seeds for birds in fall.

When mine outgrew my small garden I dug it up, split it in two. Now one is thriving at mom’s house and on at a friends in Easton.

Wild Ridge Plants in Pohatcong Township, Warren County, is owned and operated by Rachel Mackow and Jared Rosenbaum at their farm. Rachel teaches foraging and has an herbal practice. Jared is a botanist and Certified Ecological Restoration Practitioner.

Their native plant nursery is on their farm, but please make an appointment. They are an all natural, chemical free business, and source all their seeds locally. They were certified ‘River Friendly’ by North Jersey RC&D in 2018. They recognize farms that protect our shared natural resources through responsible land management.

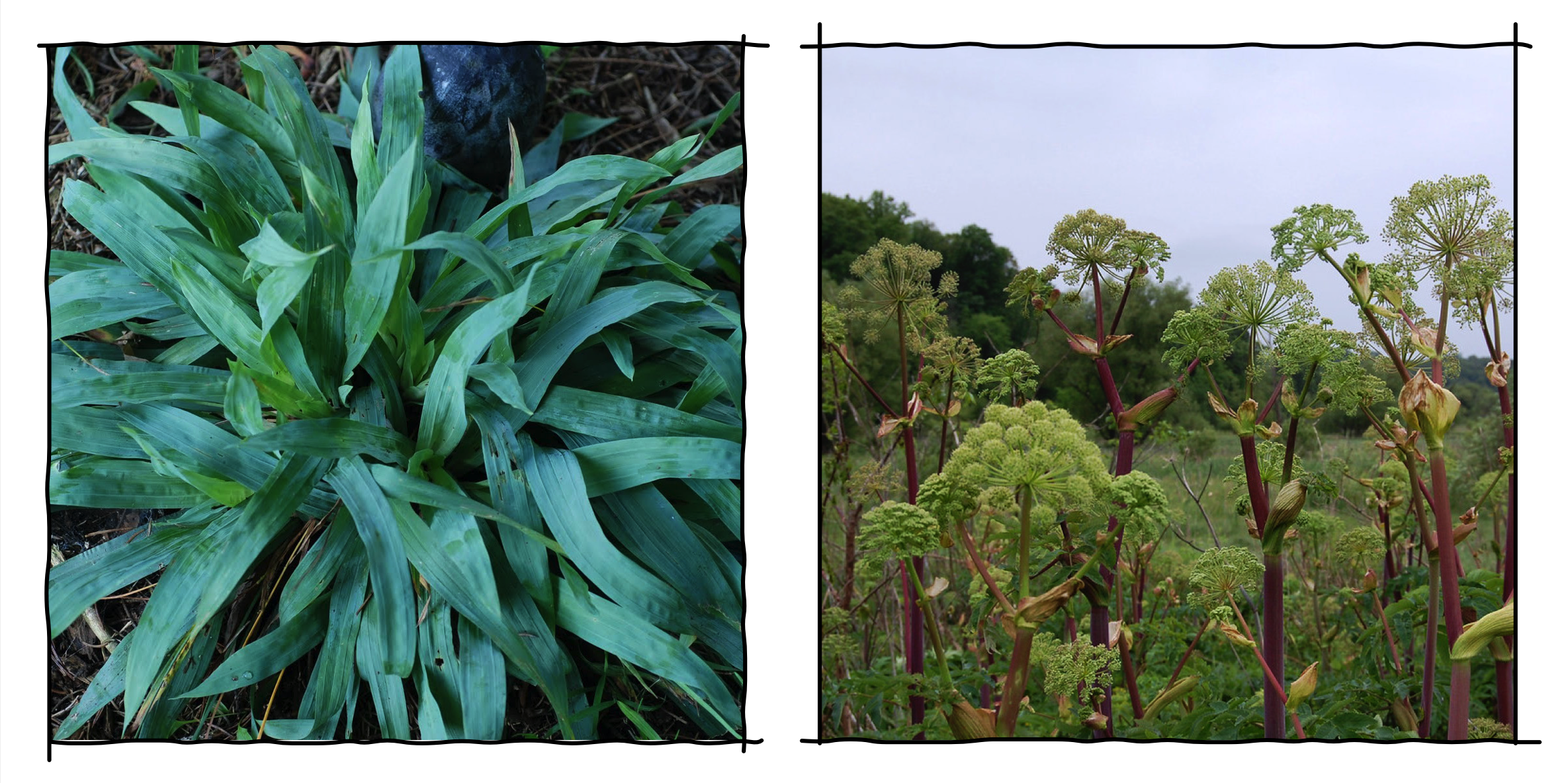

Asked about his favorite underused native Jared said ‘The more wildflower gardens I plant and the more wild areas I restore, the more I want to include native sedges in every planting palette. Sedges are grass-like plants with long leaf blades and a mounding or vase-like habit. Underground, they do remarkable work, weaving loose soil together with their fibrous roots. Sedges are the matrix into which I want to do my plantings, to build an undisturbed soil so the wildflowers feel at home, and reduce niches for weeds to recruit. Plus they have a beautiful architecture of their own’.